THE STATUE OF LIBERTY: HER BEAUTY AND MEANING

By Anthony C. Romeo, AIA

Presented on April 1, 2013, as part of the series,

“Architecture and You,” at Flushing Library, Queens

Like millions of people over the world, I think the Statue of Liberty is beautiful and also has great meaning for our lives. And tonight I’ll show why in relation to a principle I love and have seen as true—both as an architect and a man—stated by Eli Siegel, the founder of Aesthetic Realism. “All beauty,” he wrote “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

Frédéric August Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, or the “Lady in the Harbor” as she is sometimes called, brought something new to humanity, and makes for deep feeling as she appears to us from the prow of a ship or the side of a ferry, standing tall and reassuring, one arm uplifted carrying a torch.

I’m going to show that what makes it—or her—an important work of art, both powerful and graceful, is the way opposites are made one in the very structure of this famous statue—notably the personal and impersonal, freedom and exactitude, motion and rest. Looking at her history, her design and construction, I think we can learn something about what we’re hoping for in our everyday lives.

1. Personal & Impersonal

In Eli Siegel’s landmark 15 Questions, “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?” he asks about IMPERSONAL & PERSONAL:

“Does every instance of art and beauty contain something which stands for the meaning of all that is, all that is true in an outside way, reality just so?—and does every instance of art and beauty also contain something which stands for the individual mind, a self which has been moved, a person seeing as original person?”

The Statue of Liberty is clearly the figure of a woman, and this femininity is an essential aspect of her beauty. Meanwhile, she also represents something clearly impersonal, abstract. As Mr. Siegel once observed, she doesn’t just look “like any French or American girl—someone interested in breakfast! How ridiculous it would be to give her a belt or a purse on her shoulder.”

For one thing, her enormous size makes her impersonal. From the heel of her sandal to the top of the torch measures 151’11” and if you include the pedestal it is 305’6”.

When this statue was built, and for some years after, it was the tallest structure in New York City, above Trinity Church, the Western Union Telegraph Building and the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge.

People are sometimes surprised to learn that the statue which seems so massive and solid, is actually open on the inside. A seven year-old boy in the class I teach here at Queens Library, “Architecture and You,” was amazed to learn that you can walk inside the statue, up a circular stairway all the way up to her crown, and look out the lighted windows. I think he felt something that has affected every person about this colossal statue: “How could something seemingly so large also be so intimate and personal at the same time?”

Then, there is her stance and expression. Bartholdi has her draped in classical robes with a stern look, both of which accent the impersonal.

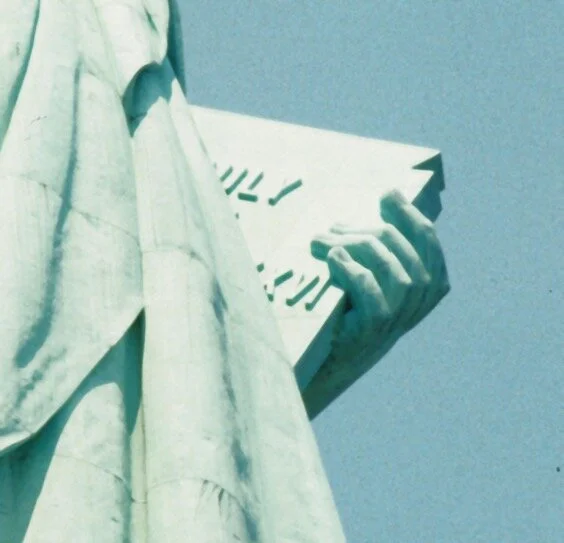

She carries a tablet, 23’8” long and 13’7” wide on which is written in Roman numerals the date of the Declaration of Independence: July 4, 1776. Her total weight is 225 tons. And when we see her in the midst of so much water and space in New York Harbor—where Bartholdi felt on his first visit to America she had to be—we feel the drama of one feminine being in relation to a vast, unlimited world.

So what makes this figure, made of metal seem so warm, so comforting? Mostly, people have associated the impersonal with something cold and forbidding, but every time I take the ferry and see Lady Liberty rising from a small island in the middle of the harbor, I feel both a sense of awe, and something reassuring, kind, and I think I’m representative in this. Is it because we feel, as Mr. Siegel asks, the presence of something “which stands for the meaning of all that is, all that is true in an outside way,” and also “a self which has been moved, a person seeing as original person?”

As colossal as the statue is, she seems at home in the harbor, at ease as she lights the way. In his book, Self and World, Mr. Siegel writes:

“Aesthetic Realism believes in the uniqueness of a self equally with its being related to all things. In aesthetics...the personal becomes the impersonal....In aesthetics the world intensifies uniqueness. It shows that relation individualizes.”

The relation of the upright, individual figure of Liberty to the wide sky, the horizon, the skyscrapers of lower Manhattan and Jersey City and the sea around her intensifies her uniqueness. And as she holds her torch aloft, she seems to honor something outside herself: the torch stands for knowledge. The crown she wears has seven radiating points which stand for the seven continents and seven seas.

2. Some History

In the summer of 1865, after the Civil War and the assassination of President Lincoln, various French writers, artists and politicians met near Versailles, at the country home of Édouard René de Laboulaye. Among them was a young sculptor named Frédéric August Bartholdi. In his book, The Epic of New York City, Edward Robb Ellis writes:

“That pleasant afternoon the conversation turned to the subject of gratitude among men of different nations, whereupon someone recited the heroic deeds of Frenchmen during the American Revolution.”

It was then that De Laboulaye suggested a monument commemorating the Declaration of Independence and Franco-American friendship. Writes Ellis:

“As chairman of the French Antislavery Society, he thought partly of the American abolitionists, whom he admired. As a historian, he looked forward to 1876, when America would celebrate the hundredth anniversary of her independence.”

Bartholdi, whose statues of Lafayette and Washington can also be seen in New York, at Union Square and Morningside Park, sailed for America with letters of introduction to raise interest in a monument to Liberty that would be a united effort of both France and America. Coming into New York Harbor he wrote:

“The picture that is presented to the view when one arrives in New York is marvelous. When—after some days of voyaging—in the pale radiance of a beautiful morning is revealed the magnificent spectacle of those immense cities, of those rivers extending as far as the eye can reach, festooned with masts; when one awakes, so to speak, in the midst of that interior sea covered with vessels—it is thrilling. It is indeed the New World which appears in its majestic expanse with the ardor of its glowing life.”

In the harbor, he made a quick watercolor of the statue he envisioned. It had to be big, like the Pyramids and the Sphinx he had seen in Egypt. And it had to be impersonal. “The details of the lines ought not to arrest the eye,” he wrote. “The surfaces should be broad and simple, defined by a bold and clear design...it should have a summarized character, such as one would give to a rapid sketch.”

For the next year and a half, Bartholdi traveled the country with Libertie’s torch shown here restored in the Liberty Museum, from New York to San Francisco and back to Washington DC, to raise interest in his Statue of Liberty. “The important thing,” he wrote to his mother, “is to find a few people who have a little enthusiasm for something other than themselves and the Almighty dollar.” This, unfortunately, was more difficult than he had imagined, and when Congress was unwilling to provide funds, Bartholdi returned to France to raise the money. The statue was to be a gift not from the government but from the people of France, and although the country was poor, in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war, French men and women gave what they could, even if it was a sous—half a penny. The equivalent of $250,000 was raised – an enormous sum for the time, and Americans were asked only to pay for the pedestal, designed by Richard Morris Hunt of New York Metropolitan Museum of Art fame.

Bartholdi himself took no payment for his many years of work on the statue—the money raised in France paid for materials and the labor of the workmen who assisted him. And so, paid for by the French people and built by working men and women of Paris, The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World was brought in pieces to Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor and finally unveiled to the world in 1886, ten years after the centennial of the Declaration of Independence. As Eli Siegel once wrote: “The lady who is the Statue of Liberty is herself, but has been accepted by travelers as representing liberty.”

3. Freedom & Exactitude

Along with personal and impersonal, the Statue of Liberty is a magnificent oneness of freedom and accuracy, freedom and exactitude.

Like most people, I once felt my freedom meant doing and thinking whatever I pleased without any restrictions. As an architect, I also had a desire to be exact, and sometimes my drawings were slavishly meticulous—you could see every brick in the building. Co-workers were amazed at the way the objects on my desk were always in perfect alignment. I’ve seen that a person can impose a kind of slavish precision on themselves to make up for sloppiness elsewhere, including the way we can take unjust liberties with other people in our minds. This was true of me, very much in relation to women.

For example, when, as a college student, I began to study Aesthetic Realism in consultations, and was turbulent about love, I was asked, “Would a woman like the way she is in your mind?” I knew the answer was No. I was more interested in having a woman serve and glorify me than I was in knowing her, and it seemed an imposition to think about who she was or what she deserved. If I had this attitude in my work as an architect, my career would have ended before it began. Imagine trying to design a building without trying to be exact about what’s required—thinking, instead, that those walls and floors and windows should be very grateful to someone so talented and freely imaginative as oneself. As my study of Aesthetic Realism continued, I came to see that knowing another person, including a woman, is an exciting adventure, and makes for a freedom I’d never felt before, both in my life and work as an architect.

Bartholdi’s work on the Statue of Liberty required great exactitude. He sketched the work, and then made a clay model.

When the public approved of this, a plaster statue one-sixteenth the size of the intended statue was constructed. Then, another plaster model one-fourth the full size was made, and divided into sections and thousands of measurements that were then transferred to an exact copy in bronze four times larger—and this is still in Paris. Charles Barnard described the process in “The Bartholdi Statue” originally published in 1884:

“The great irregularity of the drapery made it necessary to put three hundred marks on each section, besides twelve hundred smaller guidelines, in order to insure an exact correspondence in proportion between the enlarged sections of the full-size model and the sections of the quarter-size model.”

Wooden molds were then hand made by French carpenters and into them sheets of copper were hammered. Barnard writes:

“All the repoussé or hammered work, was done from the back, or inside, of the sheet. If the mold is an exact copy of a part of the statue, it is easy to see that the sheet of metal, when made to fit it, will, when taken out and turned over, be a copy...In this complicated manner, by making first a sketch, then a quarter-size model, then a full-size model in sections, then hundreds of wooden copies, and lastly by beating into shape three hundred sheets of copper, the enormous statue was finished.”

Each of these sections of pounded copper was then secured to metal framework designed by Gustave Eiffel, so that the pieces would actually “float” upon this framework—and imagine 225 tons of copper “floating” in this manner. It is an amazing fact that the statue must have this freedom in order to stand securely—it must yield to strong winds and forces of heat and cold in order to remain standing, looking solid, and carrying that torch so faithfully in the harbor.

And related to freedom and exactitude is another pair of opposites— that is, motion and rest—which are important in this statue too. Even before the actual construction began, Bartholdi’s design underwent changes during the fifteen years he thought about and worked on it. The changes made for a more beautiful relation of rest and motion, freedom and order. In 1986 the New York Public Library at 5th Avenue & 42nd Street had an exhibition in Gottesman Exhibition Hall celebrating the centennial of the Statue of Liberty. Pierre Provoyeaur, Curator of the National Museums of France was one of the organizers of this exhibition, and one of the authors of Liberty, The French-American Statue in Art and History, writes of how the statue became more powerful and free when Bartholdi came to this new relation of rest and motion:

“Bartholdi completely reworked his composition, imparting motion to the drapery rather than to the figure itself... Now the statue comprised a series of juxtapositions of movement and stillness that... took on greater dramatic force once the whole figure had been struck motionless from top to toe: one foot firm, the other striding forward; the chiton smooth, the peplum in folds; the fingers of a hand clasping the tablet of stone; the head immobile, the light radiating from it; crowning the whole, the monumental torch and its flickering flame.”

The face, and the right arm, as it thrusts upward through the sleeve, are the most dynamic and powerful points of the statue. The downward folds of her sleeve and almost agitated folds of her robe give a sense of impediment, making the upward thrust of her right arm seem like a victory. There is a drama of opposites, too, in the way she appears still when viewed from her right side, while from her left she appears to be powerfully striding forward, knee bent, heel raised, weight seemingly shifted forward.

The gathered brow of Liberty, her seemingly stern appearance, seems to be critical, and questioning. The Statue of Liberty is a reminder of our responsibility to be vigilant and see the true meaning of freedom and oppose complacency in ourselves. The centennial exhibition book points out that the Statue of Liberty has been made symbolic of both Liberty and the United States. Meanwhile Benjamin Franklin implied that you cannot love liberty unless you are interested in what all the people deserve. “God grant that not only the love of Liberty but a thorough knowledge of the Rights of Man may pervade all the Nations of the Earth,” he wrote, “so that a Philosopher may set his foot anywhere and say, ‘This is my country.’”

The Rights of Man have to do with a question Eli Siegel said must be honestly answered for Americans to have true freedom, including economic freedom: “What does a person deserve by being a person?” I think the Statue of Liberty is an illustration of the principle clearly stated by Aesthetic Realism: “that freedom is the same as justice, the same as true exactitude, the same as courageous relation.”

© Anthony C. Romeo, 1986/ 2005